In today’s episode, Jenny walks you through assessing paralysis under anesthesia, and whether or not a patient has recovered from the paralyzing effects of anesthesia. Jenny talks specific drugs used as anesthetics and what to look out for when finding out if a patient has already regained muscle control. Tune in to learn more about twitches, train-of-four, tetany, and more things to look out for when pulling a patient out of anesthesia.

Get access to planning tools, mock interviews, valuable CRNA Faculty guidance, and mapped-out courses that have been proven to accelerate your CRNA success! Become a member of CRNA School Prep Academy here!

Book a mock interview, personal statement critique, resume review and more at https://www.TeachRN.com

Join the CSPA email list here!

Send Jenny an email or make a podcast request!

—

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

Assessing Paralysis Under Anesthesia

A quick disclaimer because in this episode, we’re doing a little more clinically based type of topic. I want to make sure I’m throwing it out there to make sure you’re always fact-checking me and you’re equally looking up the doses of medications prior to administering any drugs. I hope you folks enjoy our episode and let’s get into the show. How do you monitor neuromuscular blocking agents under anesthesia? Let’s get into our episode.

—

In this episode, we’re going to continue our mini-series and dig into some anatomy, pathophysiology and pharmacology. I wanted to talk about train-of-four monitoring and essentially how to monitor neuromuscular blocking agents while you have a patient anesthetized. We’re going to get into some of the overarching concepts, and so that way, when you start your clinical rotation, you’re going to feel hopefully more knowledgeable in how to communicate your concerns or questions to your preceptor.

First and foremost, how do we figure out whether the patient has fully recovered from the paralytic? Now, there’s a variety of different types of paralytics you can give. Again, make sure you understand the differences between them all. That should be a topic for another episode. We’re going to focus on just train-of-four and how to determine whether a patient has been fully reversed from their paralytic.

Again, there are different drugs now like Sugammadex, which is amazing. Dive into the drugs, understand them well, understand what drugs they work with and how they reverse paralytic and things of that nature. When you use a train-of-four, you are assessing the patient’s tetany. That’s a sensitive test for neuromuscular function. Anywhere from 50 to 100 hertz of electricity is given to the patient, which causes the muscle to contract.

There’s something called a Double Burst Stimulation, which is a more sensitive test than tetany fade. What’s a tetany fade? If you have two electrodes on the patient’s orbicularis, which is by their eyeball, their facial nerve, you’re going to see half their face contract and twitch. You’re going to see their eye contract with tetany and if they’re still paralyzed, you’ll eventually see that eyeball and the muscles relax slowly fade. That’s what’s called the fade. You’ll see a strong contraction with a slow gradual fade. That means they still have paralytic on board, versus when you give a burst stimulation, you’re gauging what does the first twitch look like when compared to the other twitches?

The Train-of-Four

The train-of-four has been coined. See out of 1, 2, 3 and 4 twitches, where do you lose the twitch? If you do a train-of-four and you have no twitches, you’re close to 100% paralyzed. You literally have no ability to move a muscle. If the surgeon says, “Your patient is moving.” You can say, “Impossible.”

That being said, you can barely have one twitch. I’ve noticed that mostly in abdominal surgeries, the surgeon somehow frequently knows if there’s any type of muscular activity at all. They could see peristalsis going on down there or something and they’re like, “The patient is not paralyzed.” You’re like, “They have to be.” They maybe have a post-tetanic twitch but they don’t have even one twitch. How? I’m telling you, you’ll have surgeons who claim they know that they have something and it’s hindering their ability to operate.

Anyhow, lucky you, you have to experience that. That being said, if you don’t have any twitches, you’re completely paralyzed. Now if you have one twitch, maybe it drops down to 80% paralyzed and there’s a range. Maybe it’s 70% to 80% or whatever. Let’s say, at one strong twitch, you had to give a full dose of neostigmine and robinul to reverse that, you could.

You never want to reverse with neostigmine and robinul without at least one solid full twitch. Remember that. We’re going to get into where you should be monitoring their twitches when deciding to reverse. It’s different than maybe what you think. It’s common to put the twitcher up by the eyeball because it’s the most accessible. You’re at the head of the bed but the reality is it’s not the best place to gauge the diaphragm muscle in the twitches. We’ll get into more of that a little bit later. That being said, one twitch, you know that they’re reversible. You equally know that they’re still pretty paralyzed. They’re not going to buck on you or overbreak the vent.

One twitch is a good place to be. I don’t see too many reasons to take away all twitches unless there’s something or some type of case the surgeon needs it for. One twitch is pretty adequate for 95% of the cases that you will ever do for the most part. If you have two twitches, this means that the patient is still pretty paralyzed. Could they maybe move a little bit? They probably could. Could their diaphragm move a little bit? They could but they’re not going to over breathe the vents.

They may try to have a little bit of respiratory effort but they’re not going to sit up off the bed and buck and do all those crazy things. When you get to three twitches, then you have to start thinking, “This patient could significantly buck on the vent and show some respiratory drive with three twitches.” The surgeon will definitely notice it at that point if there’s something that they need them to be more paralyzed for. If they have all four twitches, then they’re going to be able to move and breathe spontaneously.

It doesn’t mean that they’re not paralyzed anymore. Remember that you can have four twitches and still have up to 70% blockade. As I said, if you have one twitch, maybe you drop to 85% or 90% and if you have two twitches, it’s 80% to 85%, and with three twitches, 75% to 80%, then four twitches is 70%-ish. Going from 99% and 97% all the way down to 70% with all four twitches, you can still have a significant blockade with four twitches but it does mean that you can spontaneously breathe.

What you’ll see is they’re never going to breathe that well. They’re going to be taking probably half the amount of tidal volumes or less than half tidal volumes. It means if they could have a tidal volume of 500, they’re going to be lucky to get 200 with four twitches without reversing paralytic. It could be that substantial. The trick with having four twitches is once you have four twitches, you then have to determine do they have fade. How much of the 70% potential blockade is left?

There’s been a lot of debate on, “You gave paralytic at the beginning of the case. It’s been four hours. Should you still have to reverse?” If you know the half-life of rocuronium, it should be out of their system by now. There’s some school of thought that you should always give at least a little bit of reversal because there could be some receptors still blocked, especially if you have someone who’s maybe a respiratory cripple. There’s an argument for both sides of the coin.

Anesthetic Drugs

Neostigmine is not a benign drug, so some people will argue, “It’s not worth the potential side effects. There’s a little bit of blockade, but they’ll be fine.” That could also be true. Again, you’re going to hear both sides of the coin argued for. I think as long as you’re matching neostigmine, you’re just giving one and one like 0.2 of robinul and 1 milligram of neostigmine, which ends up being 1 ml and 1 ml based on what they typically are standard concentration.

As long as you’re matching, you’re not going to get as many of the side effects but they are still there. You have to know that they’re still there but they’re just not there in big effects. You still have potential side effects from neostigmine. They’re not going to be the same as if you would give a massive dose of it and then debate whether it’s worth the risk of your patient having some muscle weakness. If you know your patients and their history best with their young, healthy buck, then they’re probably going to be fine.

Matching robinul and neostigmine will prevent most of the side effects, but they can still be there. Click To TweetIf they’re an older, frail, smoker, emphysema, they probably need all the receptors they can get, so just use your best judgment. Now we have the beautiful drug called Sugammadex. It’s amazing. Equally in respiratory cripples, a 100% sugammadex all day, every day, there’s no reason to use neostigmine when you have sugammadex for someone who is high-risk. It is the best way to reverse rocuronium. If you have the availability to use it, you should. The problem that I’m seeing now and it depends on the clinical facility, is some students depend on where they’re training. Their facilities almost always use sugammadex. That’s to reverse almost everyone. They’re not getting experience from neostigmine and robinul.

I’ve had students come to say a pediatric rotation and not understand the max dose of neostigmine and robinul. They’ve overdosed or don’t understand how to draw it up or match it or the potential side effects of it. Do your due diligence and understand neostigmine because you never know what clinical site you’re going to be thrown into. Not all clinical sites use sugammadex like it’s candy because it’s still considered somewhat of an expensive drug. It’s maybe on lockdown. A few different experiences of mine, it’s been different everywhere.

If I used it, I had to write a note to the pharmacy and explain why I used it, put the patient’s MRI, patient sticker on it, and everything. They need the paperwork to even use the drug. In other places, they are like, “Go take it out and use it as you see fit.” In other places, you had to make sure you had a reason for it to use it, so it depends. Back into assessing paralytic and things of that. We discussed all four twitches and a little bit of fade. If you get to four twitches and you assess that you do have a fade, you still have a paralytic on board. You need to be reversing. If it’s been six hours since you last dosed it and you test someone’s fade, I would highly doubt they’re going to have any fade, but this is how you would assess that.

Anesthesia Reversal

A negative test, meaning they don’t need a reversal, is a sustained tetany or a sustained contraction for five seconds. That’s one 1,000, two 1,000, three 1,000, four 1,000 and five 1,000. It’s a long time. It’s not like 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. You have to hold it there for five seconds and make sure you don’t see that fade. If that’s the case, cool. You don’t have to give any reversal. One caveat to this piece that I have seen that’s a problem is if you’re waiting until the end of the case to do this and to test them and they’re maybe partially in that emergence phase where they may or may not have some recall, keep in mind, that hurts. Test it on yourself. Having 100 hertz, that’s not going to feel very good. Can you imagine having that electricity going right into your eyeball and cheek area? It’s like someone is zapping you.

Have you guys ever used those bugs electrocutors? We have one. It works well to electrocute flies and stuff. Imagine you’d be electrocuted on your eyeball. It wouldn’t feel good. Keep that in mind. If you’re questioning whether or not they’re ready to extubate and you do this, I’m not saying not to do it but just be cognizant that they may or may not have recall when you zap them. Be nice. There could be other ways to assess whether they’re ready to be extubated versus shocking them.

This is why you need to be doing this well beforehand if possible versus waiting until they’re ready to pull the tube and then questioning. Maybe there is still weight from the paralytics. At that point, this tool that we have to look for tetany is cruel but sustaining contractions for five seconds will show that you have an adequate reversal of muscle relaxation. Other things you can do other than shocking them and hurting them if they’re already someone awake is making them hold their head up off the bed for five seconds.

That equally indicates that they are strong enough to pass that they’re not paralyzed anymore. I feel that’s hard to get people to do. It always makes them gag and cough because the tube then gets jammed in their throat. I feel like the head lift is a hard test to do but I have used it. It does work. I have seen it done successfully. Again, I think it always promotes this coughing and that makes the patient uncomfortable then it gets hard to gauge with their breathing because then they’re coughing. You can’t tell what tidal volumes you’re taking. It gets on this annoying rabbit hole.

The other thing too is the hand grasps. The common thing you’re going to see is to squeeze my hands. This is equally can be hard because sometimes they’re comfortable and sedated. They may be reversed from paralytic and be like, “I don’t care.” They’re maybe so comfy. They don’t care about tightly grasping your hands or they’re awake but they barely give you anything or they do one hand not the other.

It can be hard to get them to elicit the response you want when they’re still groggy and waking up from anesthesia. This is when you have to gauge on your end title CO2 and the tidal volumes you are taking. When was the last time you dosed a paralytic? Did you reverse? Did you not reverse? Could there be a chance they’re still potentially weak? Assessing is it a possibility, first and foremost? If it’s a possibility, then maybe give them an extra 0.2 milligrams of robinul and see if that improves. If it improves, you’re right. Let’s go ahead and excavate them. Keep in mind of the max dose of neostigmine is 0.08 milligrams per kilo.

Neostigmine in itself can cause weakness if you give too much of it. That is why for an adult, they say that 0.05 milligrams is always the max dose. If you are a petite little female who’s only 40 kilos, the max dose is not 0.05. The max dose is 0.08. Keep that in mind when you are dosing neostigmine. Make sure you’re cognizant of what the max dose is for that patient and their weight.

Neostigmine, by itself, can cause weakness if you give too much of it to your patient. Click To TweetIf I know the max dose for the patient, I tend to give a little bit less than that to see if that gets me to where I need to be. That way, if they do tend to still look weak, I’m like, “I can give a little bit more.” I would give the max dose if I felt like they needed it. If they only had one strong solid twitch, then it’s a max dose. These days, I prefer sugammadex. I don’t even bother with neostigmine because even with one strong twitch, giving neostigmine and robinul for reversal, it’s not as great.

Patients fills up having a little bit of weakness and it takes forever to kick in. Typically, it takes ten minutes for the peak effect and by then, you’re sitting in the OR and everyone is staring at you like, “Is this ever going to happen? Are you ever going to excavate the patient?” You’re like, “I have to wait for the reversal.”

It’s tricky to time neostigmine and they’re still suturing. You don’t want them to buck and cough while they’re still suturing. When they’re done suturing, they’re done. They want you to have the patient extubated but you’re like, “Now I’m going to give reversal.” You have to keep in mind that you have to wait around for it to kick in. How paralyzed are they already? You can usually get away with waiting to give neostigmine and robinul. They’re completely done suturing if you already have 3 or 4 twitches.

If you only have 2 or 1 twitch, you need to be giving that neostigmine enough time like ten minutes to fully kick in to make sure they’re not weak for extubation. Keep that in mind if that’s what you’re using. With sugammadex, once it circulates, it’s in and it’s instantaneous. It’s an amazing drug. I remember being so terrified when I was in clinical when I was trying to gauge a robotic case. I’m trying to gauge where they’re at. I’m staring at the screen watching these little robot hands do things.

I’m like, “They have some time left. We have another half hour left. They have three twitches. I’m going to give twenty of roc or I don’t know,” then they’d have no twitches. They’d say, “We’re all done. They’d undock the robot.” You’re like, “What? No, redock.” Now I need time because I’m thinking, “Am I going to have enough time to get this to wear off to where I can even reverse it?”

There were times where if you don’t time the paralytic well, then at the end of the case, you literally couldn’t even do anything. You couldn’t even reverse because there’s no way to reverse the paralytic without at least one solid twitch. It was critical that you thought about the timing of the paralytic. Now with sugammadex, people have gotten away from that a little bit more because they know they have a backup reversal agent that’s quick and easy. You can have no twitches and not be in trouble.

I think it’s still good to think through those things when you are dosing your medications and trying to come up with the best timing. That explained how to gauge or assess whether someone is ready for excavation or their paralytic is still on board. Now getting into the monitoring portion of it as far as how to apply the train-of-four monitor.

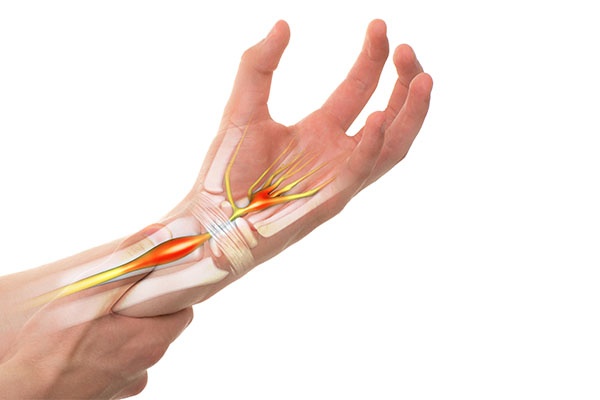

You have two areas that you would apply this to either as abductor pollicis, which monitors the ulnar nerve, which is again on your forearm area. You would put the two probes again up against your ulnar nerve and you would get the hand twitches with that. That is the best assessment for recovery. If you’re questioning if you barely have a twitch up here and you put the twitcher down on your abductor pollicis muscle, you may not have any twitches.

Should you reverse with neostigmine? No, you should not. That’s how these orbicularis oculi can trick you a little bit into thinking, “I’ll be okay.” Always check the abductor pollicis for a better indication of whether they’re going to be reversible with neostigmine with one twitch. For intubation, the best place to monitor is the eyeball. However, I’ve never seen this done. Maybe I have for experimental purposes to see when the muscle paralytic kicks in for like, “I want to show you how long it takes to have muscle paralytic.”

It’s usually a minute and twenty seconds. By the way, you can speed up the onset of rocuronium if you give larger doses but if you give more substandard, I should say, standard doses of roc usually takes a good minute and twenty seconds for it to fully paralyze. Sometimes we’re like, “Let me show you how long it takes.” They put the twitcher on the eyeball and they would put it on continuous twitch so you can see when they would lose it.

That being said, we don’t typically use the twitcher for induction. We don’t wait to intervene until they lose all twitches or anything like that. You simply watch the clock and gauge whether they have any respiratory effort anymore, then you go for it. If you put the blade in their mouth and start having the claw come up to get you, then you know they need more time. They’re not fully paralyzed yet or if their cords are closed, you get in there and the cords are completely closed. Don’t try to slam the tracheal tube through closed cords.

If that was me, I’d be mad at you. Don’t do it. Give your patient more time. Come back out and mask ventilate. You don’t want to let that paralytic kick. You don’t want to push through closed cords. That would cause trauma. You can do nerve damage with that. Those are the two areas to monitor. If you’re in the ICU, I encourage you to play with this. I would encourage you to put it both at the orbicularis oculi and the abductor pollicis muscle and see the differences between tetany, train-of-four and fade. See the differences for yourself. They’ve been on a continuous drip. It may not be as indicative as if you’re trying to let it wear off but if you ever stop the drip, I encourage you to play with trying to watch how their twitches come back.

Keep in mind that this hurts. If they’re also equally off sedation, maybe not. What’s going on the best, it would be interesting to understand and play with it while you’re working on the unit with the different types of paralytics and stuff. The orbicularis oculi is the ideal muscle to monitor during induction. That’s more similar to the central muscle. The onset of block will be similar to the laryngeal muscles in the diaphragm.

Orbicularis oculi is the better train-of-four area to monitor during induction because of how it will predict the sensitivity between the diaphragm and the vocal cords. In the reversal and recovery, the abductor pollicis is the best option because it monitors peripheral muscle. The respiratory muscles are likely to have recovered to a greater degree and monitoring peripheral muscles provides a larger margin of safety. It provides a larger margin of safety to monitor that area to gauge recovery from paralytic than the orbicularis oculi. I hope it all made sense and I hope you guys enjoyed this topic. Thank you for tuning in. I appreciate you. Until the next episode, you guys all take care and cheers to your future. Bye-bye for now.

Important Links

Get access to planning tools, valuable CRNA Faculty guidance & mapped out courses that have been proven to accelerate your CRNA success! Become a member of CRNA School Prep Academy here:

https://www.crnaschoolprepacademy.com/join

Book a mock interview, personal statement critique, resume review and more at https://www.TeachRN.com

Join the CSPA email list: https://www.cspaedu.com/podcast-email

Send Jenny an email or make a podcast request!